Alpha and Excess Return: Not Synonymous

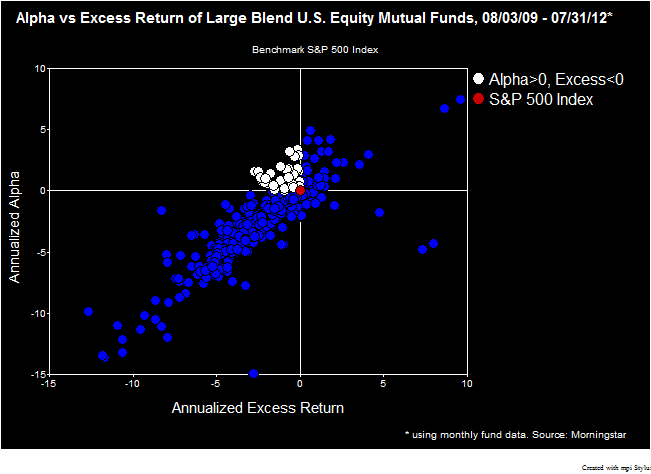

Can a fund whose alpha is positive significantly underperform the market? Yes, it can. This is a common question we receive during our clients’ Quarterly reporting, so we felt it worth addressing this phenomena – and taking a quick look at funds that gain this distinction. There is a common misconception that alpha means outperformance […]

Can a fund whose alpha is positive significantly underperform the market? Yes, it can.

This is a common question we receive during our clients’ Quarterly reporting, so we felt it worth addressing this phenomena – and taking a quick look at funds that gain this distinction.

There is a common misconception that alpha means outperformance or “beating the market”.

Sign in or register to get full access to all MPI research, comment on posts and read other community member commentary.